I love my dad, and he’s been a wonderful role model, but rather unfortunately, he set me on a path of pain and suffering — a path that was once bright with expectations. My dad is the reason I’m a Cowboys fan.

If you’re not familiar with the Dallas Cowboys, allow me to wax poetic for a moment. The Dallas Cowboys are, for all intents and purposes, a perpetually average football team, tangled in ego-driven mismanagement. They have not been a successful sports franchise since the mid 1990s, assuming your metric for success is winning championships. For the past 30 years, the Cowboys have engaged their fanbase in perpetual edging, never to actually finish the… uhm… job.

This, in essence, is the current state of artificial intelligence (AI).

The mystique of the Dallas Cowboys was rooted in their early success, with a hard re-launch in 1989 that resulted in one of the most legendary teams ever assembled through the mid 1990s. (It’s rare to have a Hall of Fame QB, RB, and WR, all in their prime, at exactly the same time.) The Cowboys have a brand that suggests inevitable greatness: “America’s Team.” This is essentially what AI has represented to computers, the internet, and general IT culture. Through the late 80s and early 90s, the mystique of the internet grew. Everyone got personal computers, and then smartphones. We were all connected. Shitposting got normal. Some of us (like me) became shitposting legends, building entire brands and careers on shitposting.

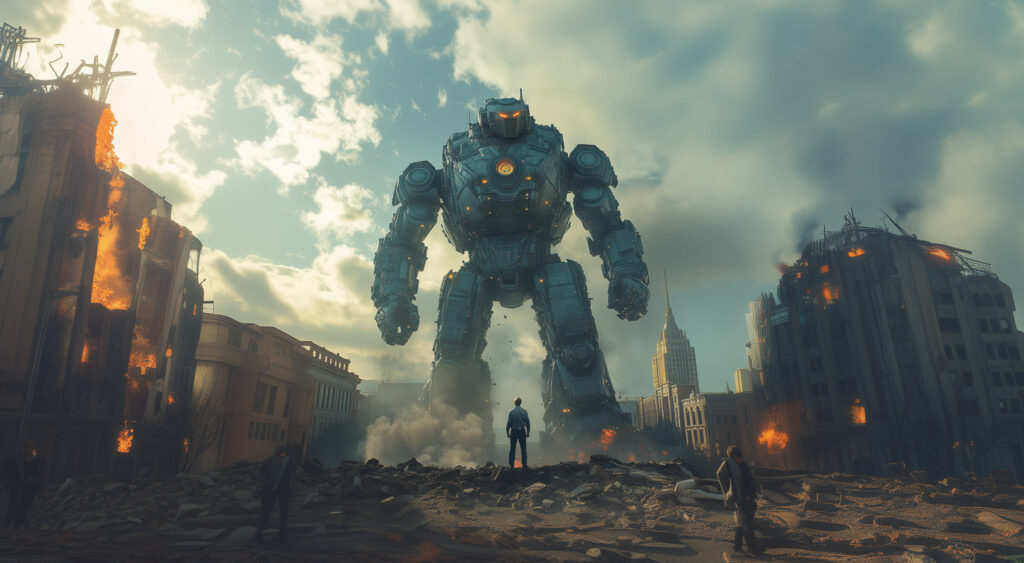

We knew that AI would arrive eventually, because the notion of super-intelligent machines helping us solve pressing problems was demonstrated by Terminator 2 — one of the rare instances a sequel was better than the original. (And somehow, more believable. The plot of the first Terminator was just crazy at face value — and not the time traveling robot assassin part of things. During the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, a dude approaches you and says he’s a time traveler, and the only way to save society is letting him raw dog you? Bold strategy Cotton. But I digress…)

Then, we went into a period of malaise. The internet and computers were ubiquitous. We started taking our connected reality for granted. I’m not trying to downplay the role of the internet and the growth of IT infrastructure in our day-to-day lives for 30 years, but what I’m saying is it felt incremental and gradual. I’m an engineer, and I work in this every day, so I feel like I’m speaking the pragmatic reality of information technology when I say there have been some cool new tools, but nothing earth-shattering.

There certainly hadn’t been a, “Whoa, this is really changing everything moment” — at least in the same way ChatGPT made us all take a step back and rethink what was possible. Large language models are unique because we all use language. It was a moment where we could interact that felt human and real. This wasn’t IBM Watson winning at Jeopardy, or Stockfish destroying you at chess. Even YOLO is pretty niche in terms of computer vision. Even though I think it’s cool for classification, it just didn’t feel as magical as conversing with a machine.

Alright, enough hyperbole. Let’s move along.

The ChatGPT moment was Jerry Jones buying the Cowboys and firing Tom Landry. It was a shock to the system.

AI was “expected to be the future” for so long, when it finally happened, we weren’t expecting it. It’s like when evangelicals say Jesus is coming back. They’ve been calling for the return of Jesus for so long, that it probably will be actually shocking when/if he returns. I’m crossing my fingers that Jesus comes back as a streamer, personally. “Chat, can we get some compassion and forgiveness? Mods, I need you to get on top of the weird anti-Semitism before I start a new Rocket League match…”

The arrival of ChatGPT (and later, Claude, LLama, and others) was a shock to our culture. It was “the future” for so long that it lost meaning.

Now that AI is here, it’s “the future of everything.” — again. Like Terminator 2 to the original Terminator, but with less raw dogging. (Or so I was told on LinkedIn.) AI is going to propel our self-driving cars, diagnose rare diseases, ingest and examine videos, and even write our college English papers. But like the Cowboys, AI’s actual track record is a mix of small (but interesting) triumphs, setbacks… and then a ton of unmet expectations and disappointments.

Right now, we are living AI’s “Dak Prescott Moment” with large language models. Dak Prescott was a 4th Round pick from Mississippi State, and he improbably went on this crazy winning streak to take the starting role from an injured Tony Romo. No one was really expecting the Dak Prescott experience, and then all of a sudden, the general malaise snapped, and Cowboys fans were like, “Wait a second, we might not suck anymore?”

This perpetual state of “it’s definitely just around the corner now” is what defines the current state of the Dallas Cowboys and AI. For the Cowboys, we have the franchise quarterback in Dak Prescott. We have Micah Parsons, the next coming of Lawrence Taylor. Cee Dee Lamb is that dude. It’s all there… but it really isn’t. The Cowboys are still led by the same failing billionaires, whose goal isn’t actually progress, but profit margins.

For AI, it’s the same exact problem. The incumbent billionaire powers that have mismanaged us into information technology malaise are the same. Microsoft, Meta, Google, AWS and NVIDIA are our Jerry Jones analogues, all chasing past greatness, with no clear vision for anything except profit. They’re not going to push forward groundbreaking products. They’re here to sell jerseys, metaphorically speaking.

Maybe you don’t remember the last time you got hyped up about “blockchain technology” changing how everything works. Remember “big data” transforming the world? Pepperidge Farm remembers. Did big data change your life? Are you regularly using any blockchain-enabled applications today?

We’re all living in the same unreality. It’s the belief that the next algorithm, the next draft pick, the next dataset, the next coach, the next pipeline run, the next touchdown… will finally push us into a new era of dominance. In both cases, the hype machine keeps churning, fueled by past glories and future promises, while the present reality remains stubbornly more complicated.

Go peruse any Dallas Cowboys fan sites or message boards, and you’ll observe the kind of childlike optimism and wonder that is contrasted more sharply with adults in abusive, codependent relationships. We are, after all, basically giant children watching other people play a game. It’s almost admirable how we lie to ourselves. Every year, despite the odds, Cowboys fans fool themselves into believing this is the season we’re going to be back. We buy the merchandise, buy the insanely overpriced tickets to Jerryworld, and engage in endless debates about why this year will be different.

The AI community has its own version of this, especially on the hellscape that is LinkedIn. Everyone writes think pieces, participates in “fireside chats” at conferences, and boasts about their AI strategy. (Side note, there is nothing more hilarious to me than management and C-Suite people telling us how AI will be transformative in flowery language. If you have never written a line of code, it shows. You’re not an AI expert. You have an MBA. Chill.)

The disconnect between expectation and reality is going to cause this AI bubble to burst, because hype doesn’t drive change. What hype leads to is more hype. Then it is followed by frustration, disillusionment, and then again—paradoxically—an even stronger belief that “the big breakthrough” is just around the corner. Because we don’t want to believe we got it wrong, so we get all hyped up again when we get any news of success.

The real question, for both the Cowboys and AI, is whether this cycle of hype and disappointment can be broken. The solution for a breakthrough is the same: The billionaires who were successful in a different era cannot be the future. Their motivations are driven by incremental, small, extractive measures. They’re never going to make a big leap, because shareholders frown upon transformative change. They want CAGR, baby. It’s easier to sell jerseys and hype than invest in what is truly required — a change in leadership, a complete tear-down, and rebuilding from the ground up.